"Abolition Is..." — A Roundtable

As the language and logics of prison industrial complex (PIC) abolitionism enter the liberal mainstream, they also become subject to increased co-optation, bastardization, and de-radicalization. Black rage, Black grief, and Black militancy are incorporated, distorted, and sold back to us as Black capitalism, Black punditry, and Black “representation” in electoral politics. Burning police precincts becomes an appeal for small budgetary concessions. “Abolish” becomes “Defund” becomes “Reform.” We make promises for more diversity and more inclusion. We issue statements and elect the “lesser” of two evils. From the academy, we get what Joy James terms “academic abolitionism” - the rhetoric of abolition so severed from any Black radical, working-class, or grassroots origins that it no longer has radical potential. “There is nothing about the academy that has revolutionary desire,” James notes in a 2019 lecture, “And if abolitionism is about revolutionary desire, then you're caught in a contradiction.” We become ahistorical about abolition. Business continues as usual.

Intentionally reconnecting with the Black radical past is one way to intervene and challenge ahistorical, purely academic abolitionism. More specifically, the study of pre-1900 Black radical abolitionist activity (subversion, rebellion, insurrection) in the Americas affirms the historical roots, present responsibilities, and future possibilities of PIC abolition. By returning to the first abolitionist movement in the Americas—a movement of Black radical resistance against unfathomable odds—I believe we can amplify corrective historiographies to make sense of abolition in our time. Using these histories of resistance as blueprints may enable us to forge new pathways forward against the enduring realities of capitalism, colonialism, and anti-Black racism that shape our lives and deaths.

The following roundtable features three young people currently organizing and theorizing around issues of PIC abolition. As recent graduates and soon-to-be graduates of New York University, we are attuned to the proliferation of academic abolitionism in our lives and our work. We all contribute to the multimedia resource hub and living archive Abolition Is…, a political education resource for students of abolition by students of abolition. Here, we compile Black radical and abolitionist projects from across time and place to create an expansive educational space beyond the confines of a classroom or the commands of an academic institution. By developing free resources for learning in our “Study Series,” centering radical young people's creations on our “Feature Page,” and hosting virtual teach-ins, letter writings, and other events for connection and community, the digital landscape of Abolition Is... offers us a platform to name, navigate, and ultimately, resist, the spread of ahistorical abolitionism.

Throughout Abolition Is…, we utilize the term “student of abolition” in acknowledgement of the profound historical significance and the inherent present responsibility of aligning ourselves with the Black radical tradition and the tradition of radical abolitionism. When considering our choice to call ourselves “students'' of abolition, I often think of something Dylan Rodriguez said in a 2016 interview:

Many student activists call themselves ‘abolitionists’ when their political agendas are fundamentally opposed to abolition! So that leaves us with the task of teaching and demonstrating what it means to inhabit the long historical responsibilities that accompany the declaration that one is an abolitionist. You have to be willing and able to say that shit to Sojourner Truth’s ghost.

As ahistorical, de-radicalized forms of PIC abolition are promoted in the mainstream, we reflect on the following questions: Why should we, as students of abolition, be (re)turning to and (re)considering the archive of slavery abolitionism in the Americas? How can we be utilizing the archive of Early American history in the present? What insights, affirmations, and/or warnings can folks fighting for the abolition of prisons and policing learn from mobilizations against chattel slavery in the pre-1900 Americas?

Jadyn Fauconier-Herry is a writer, researcher, and member of the Abolition Is… team. She graduated from New York University in 2020 with a BA in Social and Cultural Analysis and English and American Literature, earning High Honors for her senior thesis: “Abolition Is…: Theoretical Origins and Departures of Prison Abolitionism and the Modern Prison Abolition Movement in the United States.” Follow Abolition Is… on Twitter @Abolition_Is and Instagram @abolition_is.

...

In moments of confusion or uncertainty, now and again I find myself turning to the words and work of Saidiya Hartman, a writer and scholar in the discipline of Black studies. Among her many notable texts is Lose Your Mother, in which she theorizes the “afterlife of slavery”: a concept that illustrates the omnipresent, enduring legacy of the Transatlantic slave trade. Hartman argues that enslavement in the Americas, despite hegemonically being considered a phenomenon of the past, adversely shapes present-day race relations, social structures, power hoarding, what is heralded as “the archive,” and even individual processes of Black self-making and self-determination.

In endeavoring to trace the historical lineage of contemporary radicalism—with a particular intent to marshal a corrective analysis that centers Black radical organizing and study—I find Hartman’s use of the word “afterlife” useful. By invoking language traditionally used to describe spiritual reincarnation, Hartman implies a sort of haunting interminability regarding conditions of Black subjecthood, degradation, and alienation. There is, she suggests, something about the global organizing principle of anti-blackness that completely transcends space-time as we have come to understand it. Thus, if the seeds sown by enslavement, empire, and colonial violence grow and multiply (and do so repeatedly over time), modes of resistance to these conditions so too germinate, flower, and evolve in direct response. In other words, modern Black struggle demands to be located within the broader continuum of the long withstanding Black radical tradition: a ritual and history of methods, both theoretical and practical, that are staunchly anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist. Rebellion, revolt, and insurrection are in no way anomalies and are in no way new.

To say I have been deeply inspired by Hartman’s intellectual endeavors would be an understatement. Yet I would be remiss if I neglected to acknowledge her status as an academic—specifically an academic at Columbia University, which, earlier this year, received $5 million in grant funding to establish the Racial Justice and Abolition Democracy (RJAD) project (Hartman is in no way affiliated with the initiative, and has previously been vocal about the political and liberatory limitations of academia). RJAD is defined as a “multi-disciplinary curricular program” seeking to problematize racism in the criminal punishment system. It features a working curriculum that aims to facilitate deeper understanding around PIC abolition. To some, this may seem like progress. I feel strongly that, like many institutional bodies, Columbia University likely thought it socially pertinent (and culturally topical) to respond to the urgent movement work that took place in 2020, in order to feign a façade of compassion. But what Columbia and RJAD fail to reconcile is the reality that Black people excluded from the academy have been naming, resisting, and responding to carceral terror for centuries. That a working “formal” definition of abolition can emerge from the university at all indicates an intensely violent historical and ideological disillusionment with the true roots of radicalism (none of which, despite the insidious adoption of language that might covertly suggest otherwise, stem from the academy). This is the plight of academic abolitionism, as it is defined by philosopher and academic Joy James.

James asserts that when revolutionary struggle is airbrushed from narratives of resistance to state violence, we risk losing the critical political austerity of our social movements—especially by appeasing “pragmatic compromises” that have grown increasingly popular among the general public, but that undermine the radical quality of our demands in earnest. This concerted erasure is unjust, unfair, and profoundly exploitative, not to mention ahistorical. In response to this co-optation and bastardization, I wish to conclude by attending to that which could never be codified by, legitimized through, or held within any institution or entity: subversive organizing strategies and fugitive study.

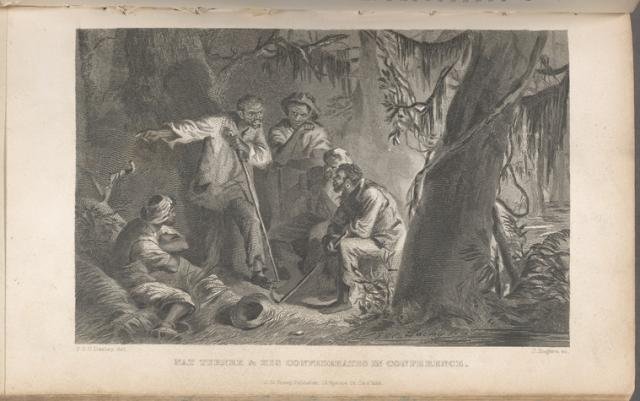

Seeking examples of the sorts of engagement I described above, I looked to “Subversion & The Art of Slavery Abolition,” an open access online exhibition curated by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The virtual gallery features photographs, letters, paintings, and illustrations documenting the creative and dynamic ways then-enslaved abolitionists built community and resisted their conditions of containment. Of the pieces included in the collection, I was most interested in a manuscript engraved by John Rogers titled “Nat Turner & His Confederates in Conference.” The image depicts Turner in conversation with four co-conspirators, two of whom wield bow staffs (Turner included). The individuals pictured emote strongly and seem to be embroiled in intense conversation. They are alone together, shrouded beneath a blanket of foliage and fog. Turner gestures to his right as if to direct someone accordingly. The comrades appear pensive. They are few of many, all planning something.

Morgan Smith is a writer, youth advocate, DJ, and member of the Abolition Is… team. She graduated from New York University in 2020 with a B.A. in Social and Cultural Analysis, Spanish, and Urban Education Studies, earning High Honors for her senior thesis, “Black Existentialism: Alternative Meditations on Black Being, Transgression, Rebellion, and Freedom.”

...

Vámonos, borinqueños,

vámonos ya,

que no espera ansiosa,

ansiosa la libertad.

¡La libertad, la libertad!

Regardless of their ideology, every Puerto Rican has heard the song “La Borinqueña,” written by the pro-independence activist Lola Rodríguez de Tió (1843-1924) in 1868. Emblematic of the independence struggle on the island, the melody went on to become the movement’s anthem, and de Tió one of its pioneers: a feminist, poet, journalist, and abolitionist. To reflect on de Tió’s life is to reflect on Puerto Rican resistance ––one that has always been uniquely artistic and unwavering, from the Spanish colonization to the American one, which still stands 123 years later.

De Tió’s firm beliefs in Puerto Rican sovereignty and the abolition of slavery prompted the Spanish-appointed government to banish her from her homeland twice: first in 1867 and again in 1889. She spent her exile in Venezuela, New York, and eventually Cuba, where she joined the Cuban fight for independence. A free Havana became her adopted home; she described Puerto Rico and Cuba as “de un pájaro las dos alas” (a bird’s two wings). De Tió rejected gender roles and became one of the first of many women to participate in the male-dominated independence movements on both islands. During the Cuban war, she was the secretary of the Club Caridad (1895-1898), which helped combatants engaged in fighting the Spanish regime. She also organized a chapter of the Red Cross.

By reading de Tió’s journalism, music, letters, and poetry, one becomes aware of how contemporary examples of resistance in Puerto Rico are grounded in the island’s mobilization against Spanish dominion and its conditions, including slavery. In pre-nineteenth century Puerto Rico, freeing the island from the Spanish crown was closely associated with abolishing slavery. The Spanish fettered the island as a colony while it kept a portion of its population in shackles. The number of enslaved people on the island in the nineteenth century hovered between 40,000 and 50,000, somewhere between 6-12% of the population. De Tió, along with other revolutionaries of the 19th century, mobilized against slavery in creative ways. De Tió used her articles, poems, and songs to call for a free country, which could only exist and prosper if all its people were emancipated. Puerto Rico abolished slavery in 1873, the third to last territory in the Americas to do so. In response, de Tió wrote the following in the La Igualdad newspaper published in Cuba:

Yo siento verdadera satisfacción en pensar en Puerto Rico, los sentimientos democráticos están infiltrados en todos los corazones y que la abolición de la esclavitud encontró allí apóstoles abnegados y decididos, que con vivo entusiasmo llevaron a cabo el triunfo de las más santa de las causas––¡la libertad del esclavo!

I feel great satisfaction when I think of Puerto Rico, the democratic sentiment has infiltrated the hearts of all Puerto Ricans. The abolitionist movement found self-sacrificing and determined apostles there, who with lively enthusiasm carried out the triumph of the most holy of causes: the freedom of the slaves!

Over a century later, Puerto Ricans are still implementing the creativity of our ancestors. In the summer of 2019, the island experienced two weeks of intense protests against then-governor Ricardo Rosselló for corruption. Published transcripts of a lewd chat between Rosselló and his top aides, in which they mocked everyone from political rivals to those who died after Hurricane Maria, compounded the scandal. The island demanded and won his resignation after the FBI arrested two top officials from his administration on dozens of corruption charges. Beyond the massive marches, the protests took new forms: perreo combativo (combative twerking), yoga, scuba diving, cacerolazos (pot bangings), horseback riding, kayaking, and more. As protesters, we reclaimed our bodies, our island, and our history. In the case of Puerto Rico, (re)turning to and (re)considering the archive of slavery abolitionism allows us to (re)imagine ways of organizing for our sovereignty.

Paola Nagovitch is a Black and Puerto Rican journalist, student of abolition, member of the Abolition Is… team, and current graduate student at the newspaper El País in Madrid, Spain, who has written about Latin American social and cultural movements and politics. She graduated Magna Cum Laude from New York University with High Honors in Journalism and Politics. Her undergraduate thesis title is “Turning Anguish into Activism after Femicides in Puerto Rico.” Follow her @paolanagovitch.

...

I’m sorry I’m going to leave you

Farewell, oh farewell

But I’ll meet you in the morning

Farewell, oh farewell

I’m bound for the promised land

On the other side of Jordan.

Bound for the promised land.

Harriet Tubman sang these words as a warning to her friends and relatives the night she fled the plantation to pursue freedom. In the presence of slave masters, Tubman disguised her intentions with the false assurance of returning. Her bid farewell marked the onset of her fugitive practice—freeing not only herself but leading other enslaved people to freedom. Under the cover of night, she was “everywhere and nowhere, north and south, invisibly present across the landscape, in the last place they thought of.” Tubman’s fugitive practices broke from the white supremacist racial order, affirmed her own agency, and attempted to “make a way out of no way” amid the racist, colonial project of chattel slavery.

Black fugitivity is both an ethical position and an insurgent practice that refuses state power. From the earliest days of chattel slavery, African and African-descended people have used fugitive practices to resist the violence and domination borne of the plantation. As Dylan Rodríguez reminds us, mobilizations carried out under the conditions of confinement and captivity, like Tubman’s raids on plantations, are the foundation and original site of the imprisoned Black radical tradition and the broader Black radical tradition at large. Students of PIC abolition can learn from the long history of Black fugitive practice.

When re-considering the archive of slavery-era abolitionism in relation to the present-day movement for PIC abolitionism, scholars should be careful not to obscure the distinctions between each system of social control. Liberal and progressive circles often position the current PIC in the United States as an extension of early American chattel slavery. On this point, Ruth Wilson Gilmore explains, “The problem with the ‘new slavery’ argument is that very few prisoners work for anybody while they’re locked up. Recall, the generally accepted goal for prisons has been incapacitation: a do-nothing theory if there ever was one.” Incapacitation through the use of imprisonment differs from chattel slavery, which functioned primarily to extract and exploit the labor of enslaved people. Even Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, notes the pitfalls of the “new slavery” arguement as an articulation of the present-day U.S. careral regime. She admits, “saying that mass incarceration is the New Jim Crow can leave a misimpression […] Each system of control has been unique—well adapted to the circumstances of its time.” While jarring analogies can be somewhat useful for public consciousness-raising work, “new slavery” and “new Jim Crow” arguments are limited and often erode key differences between chattel slavery and the contemporary carceral state.

Rather than basing critiques of incarceration on the historical continuity between enslavement and the PIC, students of PIC abolition should interpret and experiment with the practices of fugitivity Tubman and her co-strugglers engaged in during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Just as Tubman knew the system of enslavement would not dismantle itself willingly, the U.S. nation-state is not going to indict itself for the violence it sanctions and enacts through the PIC. Tubman teaches us that freedom is never willfully given—it is taken through autonomous, principled acts of rebellion.

As we near the first anniversary of the 2020 summer uprisings—one of the largest protest movements in U.S. history—the U.S. government and institutions invested in upholding racial capitalism continue to experiment with ways to dilute and de-radicalize the revolutionary fervor of PIC abolitionism. The self-preservationist instincts of the state and neoliberal universities have kicked into high gear to ensure their collective longevity. In the first three months of 2021, Mayor De Blasio announced a police reform plan in which “City Hall and the NYPD will engage with reconciliation and restorative justice scholars and practitioners to devise and execute an authentic, participatory acknowledgment and reconciliation process at the city and precinct levels.” As Morgan Smith acknowledged above, at Columbia University, law and sociology professors received a five million dollar Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant to create a new “Racial Justice and Abolition Democracy” curriculum. In the face of state co-optation, the academic commodification of grassroots struggle, and popular misunderstandings of the political commitments of “revolutionary abolitionism,” we must retain the political clarity of our abolitionist compass. Just as Tubman was strategic in her fugitive movements throughout North America as she pursued liberation, we must remain equally invested in maintaining the integrity of our political vision by being critical of how we hold the line on PIC abolition in our political lives.

As the fall of U.S. empire nears, one day, we will all say a final farewell—as Harriet Tubman did—and be “bound for the promised land.” Until then, as Mariame Kaba says, “may tomorrow bring us more justice and some peace.”

Dylan Brown is a Black writer, organizer, and student of abolition. He is a member of NYU’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study Class of 2021. He earned his BA pursuing a self-designed course of study titled “Critical Race Studies and Decolonial Frameworks of Black Resistance” and recently completed a senior thesis project titled, “Revolution and Reaction: San Quentin, George Jackson and the Imprisoned Black Radical Tradition.” Follow him @dylbrown24.

...

Suggested Resources

Abolition Is…, “Study Series”

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Abolition Geography (forthcoming)

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Restating the Obvious”

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother

Saidiya Hartman, "The Territory Between Us: A Report on ‘Black Women in the Academy: Defending Our Name: 1894-1994"

Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments

Jeffrey Insko, Michael Stancliff, Jeannine Marie DeLombard, Joy James, Brigitte Fielder, Jennifer C James, Teresa A Goddu, "Abolition’s Afterlives"

Lola Rodríguez de Tió, Mis cantares

Joy James, "Airbrushing Revolution for the Sake of Abolition"

Joy James, “The Architects of Abolitionism”

Joy James (ed), Imprisoned Intellectuals

Mariame Kaba, We Do This 'Til We Free Us

Fred Moten and Stefano Harvey, The Undercommons

Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism

Christina Sharpe, In the Wake

Dan Berger, Captive Nation

Abolition Collective, Making Abolitionist Worlds